When I first came to visit the Swedish coast, along the Baltic Sea, one could occasionally find bits of amber mixed in among the pebbles on the sand. I was told that this was because the floor of the sea was once home to a pine forest. We were holding the traces of the sap of trees that grew there a million or so years ago.

Last week, a guest casually pointed out a fossil in the stone steps that lead up to my doorway in the countryside. “It’s local stone, did you know?” he asked. “It usually has fossils. Let’s take a look.”

One long ridge on the surface of a step that I had vaguely assumed was due to the wear and tear of footsteps is apparently the cone-shaped shell of a long-extinct octopus. “The creature that lived in that shell was probably alive four or five million years ago,” my guest told me.

Then we all went in and had coffee and talked about observing how gardens change from year to year. We talked about the specifics of grasses and wildflowers, how this particular plant grows in these months, and what nourishment it does or does not put back into the soil after it dies.

I find myself moved by the general cycle of flowers in the meadow, and also by the specificity of the single octopus shell in the stone. With the latter, it is the sense that this actual creature, a living, feeling, thinking thing, once occupied this precise spot, even as the spot itself has moved around: the stone from the quarry, the quarry through glacial movements, the continent through continental drifts.

I once looked up this bit of land to see if dinosaurs ever lived here. Yes, but at that time, this piece of this continent was apparently where Latin America is today. So the dinosaurs lived here, but here was elsewhere, like the small octopus in its abandoned shell on the front steps of my house.

I find myself also with a sense of having drifted, like a continent, still rooted in myself and memories like the octopus shell in the stone but also far away. Sometimes, when the wind comes in through the windows in my house, or the fog covers the land the way fog used to roll off of the wild Pacific in Bolinas, in California, where I grew up, I could be there as well as here, or in certain parts of New England where I’ve lived over the years.

Other times, like when I fail to read the local weather and can’t guess what time the rain will come, as I would have been able to where I grew up, I am reminded that here is not there, that I have traveled. But, like the traces of the little octopus. I carry myself with me wherever I go.

Being touched by a single octopus as much as by waves of wildflowers has to do with the capacity, the need, to rejoice simultaneously in the specifics of an individual and in the value of all individuals, even when only encountered in a field of thousands.

With that thought, I had intended to segue here to some tiny specific memories, memories that have belonged “only to one [person] once,” as Larkin puts it.

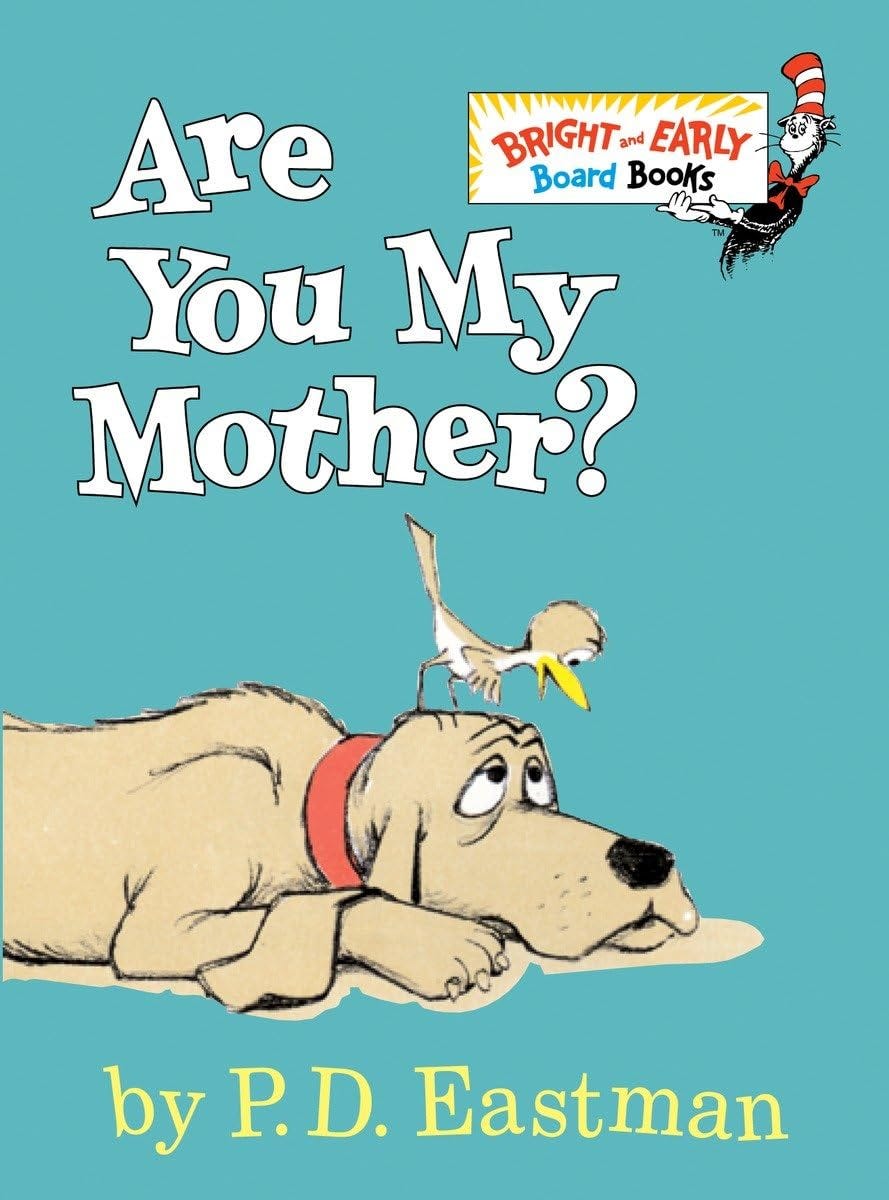

In fact, the book-related part of this essay was going to center on one of those, about learning to read because of sheer frustration that no one else took seriously enough a picture book called “Are You My Mother?”

If you are not familiar with that, it is about a baby bird who emerges from his egg while his mother is away from the nest. He spends the rest of the book walking around on the ground — having fallen from the nest — trying to find her.

He doesn’t know what she looks like, or what anything else in the world looks like either, having so far only experienced the inside of an egg.

He asks everyone and everything he meets, “Are you my mother?”

For instance, he meets a dog.

“Are you my mother?” he said to the dog.

“I am not your mother. I am a dog,” said the dog.

Eventually, by a series of happy coincidences, he ends up back in his nest, just moments before his mother returns.

When this book was read to me I believed passionately that, despite the funny bits, it was a tragedy, at least until the happy ending. It filled me with intense emotion. He cannot find his mother. It was the worst thing that could be imagined, as tragic as I could understand the world to be. (I was two or three.)

No one who read it to me seemed to grasp the pathos. They smiled while reading it, and kept the tone of the inquiry light and curious instead of urgent and desperate.

One of my earliest memories is of demanding to learn to read, purely so that I could do the line readings to myself with the appropriate amount of deep emotion.

I never told anyone why, so while there are many family stories of me learning to read at age three, the knowledge of the reason for it existed only in the grooves of my mind, until I wrote it down last year, and now again for you here.

So that was one memory. I wanted to give you some laughter, after all of that with fossils and continents and so forth.

Also, outside the window here right now, the wildflowers, above all the tall wild daisies that everyone calls prästkrage (“clerical collar”) have taken over a large chunk of the garden and are swaying in the wind under the sunshine.

I wanted to give you that also.

I thought of talking about law today, too. That would have centered on standards that assert the value of all of us as human beings, both as individuals and as existing in a group like the flowers in a field. Those standards are what I taught and worked with for a long time, and they seemed a natural extension of where this essay started out.

But in truth, it doesn’t feel right to finish out the piece today with any of that. So, no more memories, no law.

Instead I am going to leave you, along with the octopus and the meadows, with two well-known poems by William Wordsworth.

The one centers on the importance of someone specific, individual, represented by a single violet, a single star.

The other rejoices in the glory of abundance, the beauty of things witnessed as a group, in the thousands, “Continuous as the stars that shine/And twinkle on the Milky Way.”

Wordsworth’s poems are here:

She Dwelt among the Untrodden Ways

She dwelt among the untrodden ways

Beside the springs of Dove,

A Maid whom there were none to praise

And very few to love:

A violet by a mossy stone

Half hidden from the eye!

—Fair as a star, when only one

Is shining in the sky.

She lived unknown, and few could know

When Lucy ceased to be;

But she is in her grave, and, oh,

The difference to me!

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45549/she-dwelt-among-the-untrodden-waysI Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o'er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed—and gazed—but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45521/i-wandered-lonely-as-a-cloud Many thanks to

, , , , and for recommending Pen, Book and Garden: Notes from Linnesby to their readers.If you would like to explore other publications on Substack (the platform these essays appear on), you will find some suggestions here:

Recommendations

I have hesitated over how to provide recommendations to other Substack publications. The Substack platform has an automated system for doing that, in which new subscribers to publications like this one are immediately encouraged to subscribe to the writer’s list of recommended publications. That is fine for those who are already familiar with the platf…

For some recent essays you might have missed, see here:

On Delighting in Permanence

Once when I was a student I was taken, with a few others, to visit an elderly man in a small office on the top floor of the library. He was introduced as Albert Lord. He spoke to us for a few minutes, then played some recordings that he had helped another scholar, Milman Perry, make of singers of living oral epic in then-Yugosl…

Bolinas

When I moved to my little village in the Swedish countryside, I realised that in some ways I was giving myself a redo of the key years of my childhood. I lived in Bolinas, California, from when I was 7 to when I was 12. This was in the 1970s, when the hippie era was still in full swing and …

What a lovely post. I feel for your three year old self, being so worried for the baby bird. I remember having The Ugly Duckling read to me as a child and being distraught that the other birds were so mean. I was not consoled when it turned into a swan. I love daisies and daisy-type flowers in the garden, your meadow sounds heavenly.

I am enjoying the discussion in the comments as much as I enjoyed this wonderful piece. Thank you for brightening my day.