Bolinas

Memories of a hippie childhood

When I moved to my little village in the Swedish countryside, I realised that in some ways I was giving myself a do-over of the key years of my childhood.

I lived in Bolinas, California, from when I was 7 to when I was 12. This was in the 1970s, when the hippie era was still in full swing and especially so in Bolinas, which had more hippies than non-hippies, as well as a slew of writers: poets, mainly, but Richard Brautigan was there around then, and probably other novelists I don’t know of. Laurence Ferlinghetti had a house at the far, far end of the dirt road that crossed ours, on the rise of land known as the Mesa. Beyond the Ferlinghettis’ house, which was mostly empty by the time we moved there, were only the cliffs and the sea.

Bolinas was beautiful, and wild, and untended. I experienced complete freedom there, but in many ways was untended myself.

In my little house in Sweden, I found myself recreating the life I’d had then, but better, more protected. In Bolinas, I had slept in a shed that was largely porous to the outdoors (a good thing in some ways) and had been terrified of the large insects called spider hawks that flew in every night, drawn by the light of my kerosene lamp. In the house in Linnesby I immediately put screens on the windows, so that I could have that access to the outdoors, but minus the flying daddy-longlegs.

In Bolinas, one came and went as one wanted, and no one in the family really noticed. In Linnesby, my elderly neighbour W., retired and bored, kept a watchful, protective eye on me and my house. When my lights went off at night, he noticed from his upstairs window, and I knew that it made him happy that I, like him, often had mine on well into the early hours of the morning. If a day went by when I didn’t go out, I’d get a phone call, or a knock on the door: “I just wanted to make sure that you’re alive,” said with a twinkle.

When I moved into the little house here I bought a few lamps from Ikea that look like kerosene lamps, but actually are electric. One can lean over them without fear of singeing one’s hair, and they can be left on when one is not in the room, and they do not need to be refilled.

It was when I bought them that I realised how much I was trying to recreate and reinvent and in some ways maybe even replace in my memories the more complicated aspects of a hippie childhood. The fake kerosene lamps were just a symbol.

But this essay isn’t actually about Bolinas (yet), nor is it about Linnesby, or about my neighbour W. It shares instead some pre-Bolinas memories, the ones that would be in the early chapters of any kind of personal memoir of those days. And, in some ways, it’s about my father, who is on my mind just now.

Sometime in the late 1960s my parents moved to California, where they bought two pieces of rural land near a small town up north in Humboldt Country. The first, the main one, was for a house that they planned to build themselves. It overlooked dramatic cliffs down to the sea. I cannot picture the cliffs directly in my memory, but the landscape comes up, I think, in the dialogue of the film My Dinner With André. In any event, a jolt of recognition came with hearing the word-pictures there.

The land wasn’t in a village, just a cleared bit of space by the cliffs. I imagine, though am not sure, that there was forest around it. These are among my very earliest memories, probably from when I was about two years old.

What do I remember is that on that piece of land my parents built a small wooden cabin with two rooms, one above, one below, that we slept in as they were working on the house.

Or it may that the cabin was already there when they bought it. Whatever the origin, I remember sleeping in it, and the bats that flew out from the upper story and circled around it at dusk.

For the house itself, I don’t think that they ever got much further than laying the foundation. In my memory the foundation was huge, this vast expanse of concrete like a mesa in the open field beside the cabin. Likely it was quite small really, but one is so tiny at that age; everything is big, and space reaches on forever.

Those are my only independent memories of the house and its land: the bats flying out of the cabin at night, and the expanse of the foundation, which one could play around on during the day or sit on to look at the stars at night.

My parents always said that when they worked on the house they hung a cowbell around my neck so that they would hear if I toddled too far away, and especially too close to the cliff. Presumably my brothers were old enough then that they didn’t need this approach.

The other piece of land was a short drive away. It was larger: 40 acres, I think. We always referred to is as “the 40 acres” or “the 30 acres” or “the 20 acres” — whatever the actual size was, which I’ve forgotten now.

As I recall it had no cleared space among the trees except for a gap at the very centre, a long, long walk away from the road (but again I was tiny — funny to think back and realize that it may have been only a few steps from the edge, in reality) where a young woman was living alone in a small cabin.

In my memory it was a tiny cottage, just one room, and the woman was very young indeed: 20, or in any event in her early 20s, though where I got that from I have no idea.

She had a kitten — this part I am more certain of — and when I asked what it was called, she said that its name was Little Shit. And she did indeed call it that when she spoke to it while I played.

I don’t know whether we visited there one time or several times, but I remember thinking that this woman was both cool and a little scary, which was not the last time I thought that of someone.

I do know that after we moved away, to the house in Berkeley where the rest of my very early childhood took place, whenever we spoke of going to those acres, my first thought was always a hope that I might get to visit Little Shit again.

I think that my parents must have been near the land there, though perhaps not on their own land yet, even before my memories begin, because that is where the ocelot bite took place.

The family was camping somewhere in Humboldt County then. One night, as the story was told, an ocelot slunk into the open tent and attempted to drag me away by the back of my neck, the way a mother cat carries her kittens.

My parents fought the animal off while pulling me back, and it fled away again into the forest. They rushed into town where a doctor — sometimes they said that it was actually a veterinarian, not a physician — examined the bite and started me on rabies shots.

The ocelot was eventually found in the woods, and its story was determined.

Apparently it had been raised from kittenhood in the house of someone who lived nearby. The owner had grown bored of it and released it out into the wild, which it had no experience of. Of course it had starved. When the authorities succeeded in capturing it they determined that it was terribly hungry, and probably lonely and terrified, but not rabid.

We never knew whether it was trying to take me away as dinner, or to kidnap me to raise as its own. I prefer the second possibility.

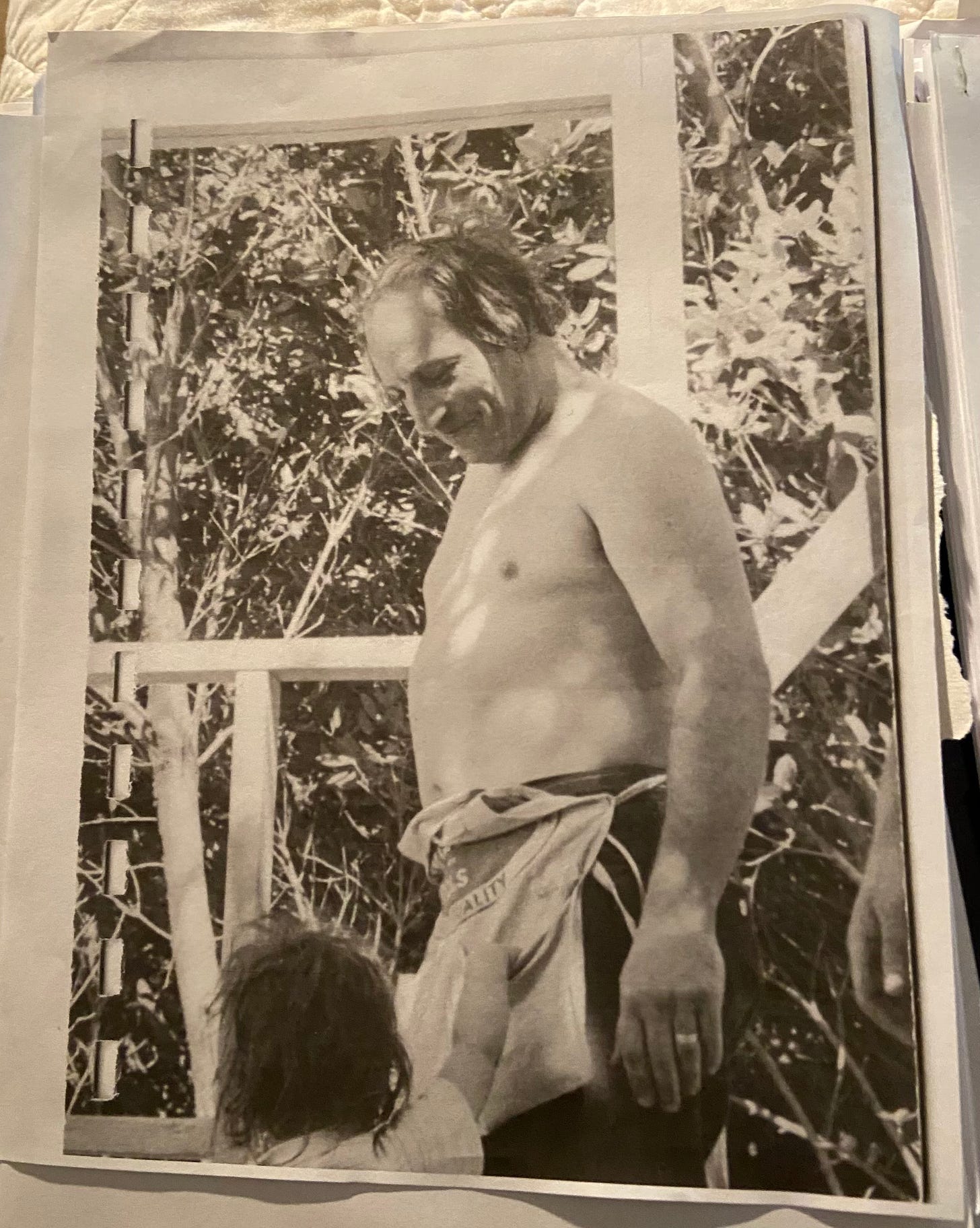

We have family photos that my parents took while they were working on the house a bit later, maybe even after my memories begin. In one of them, my father, in blue jeans, and shirtless in the sun, with a tool belt slung around his waist, is smiling as he looks at me, not seeing the picture being taken, and I am beside him, reaching up to take something out of one of pockets of the tool belt.

In one of his last pieces of writing, after he had turned 90, before the final illness but when it was already clear that mortality was looming one way or another, he wrote to a friend that he had been thinking of what photo might be used to announce his death on Facebook.

He mentioned that it was that photo with me that he had in mind.

Some recent essays that might be of interest:

On springtime, fathers and loss

Two years ago I missed the spring here in my little village. My father started his final illness in April that year, and passed away in the later part of the month. A great deal needed to be done where he and my mother had been living. By the time I returned to the house and the village, it was the middle of summer.

A translated poem, and memories of the poets Kenneth Koch and Brigit Kelly

A very long time ago I took a course in twentieth century poetry with the poet Kenneth Koch. It’s funny how some things stay and others vanish. I remember moments of that course strongly: one of them was Koch’s irritation, after assigning Yeats’s “Down by the Salley Gardens,” that no one in the class had bothered to…

An added thought: I came up with the pen name “Linnesby” for this village in Sweden after great thought, based on the Swedish word for flax and the common town-name ending “-by.” (Have written about that in more detail elsewhere on the Substack.). But on rereading this, I see for the first time that it shares all of its consonants with “Bolinas.” That is more than a little disconcerting.

Wow, the story of being dragged away by the Ocelot is extraordinary and a brilliant example of an ‘what if?’ Start of a strong or a novel. What if she had succeeded and tried to raise you as her own? (And it makes me so sad to think of her being abandoned after raised as a pet). That pic of your dad is lovely. And I love the detail of the cow bell around your neck.