Two years ago I missed the spring here in my little village.

My father started his final illness in April that year, and passed away in the later part of the month. A great deal needed to be done where he and my mother had been living. By the time I returned to the house and the village, it was the middle of summer.

That lost spring became part of my internal clock. Something in my unconscious systems conflated the missed springtime with all of the other losses of that year.

The failure to see the apple trees’ first year of blossoms, or to experience the time between when hägg flowers stop blooming and lilacs begin; the failure to see the lilacs in bloom at all, or to sit under the scent of the petals on the wild plum tree, or to see the tulips show their colours, all became a stand-in for everything else that had happened.

It wasn’t just my father — as if that could be a just — that I lost that spring. The death itself, and everything around it, shattered me. I spent the next two-plus months while I was away dealing with what needed dealing with falling more and more apart inside, like a clockwork automaton whose cogs are falling out of their places in the internal machinery, with nothing to hold them in the spots where they ought to be.

When I left here that April I left behind the man I had been seeing, who had come to down to care for me and whose physical hold seemed as though it was keeping me in one piece. If you have always had a partner, or always had someone to hold you when times are bad, you may not realize what a lifetime of being without that, of not ever having arms around you, of always being on the margins of other people’s personal lives, can do to the body and the soul; or how having it, even at the most terrible times of one’s life, can be the difference between survival and non-survival.

When I got back in the middle of the summer, I had been without being held, and without being central for any other human being, for months. The relationship had ended while I was away, and so coming back gave me the house, and my world of friends and neighbours, but it gave me no arms around me, and I wasn’t sure that it wasn’t too late for the internal pieces to be set back into place again.

Two years later, the first signs of spring seemed to evoke an automatic response of “enjoy it while you can,” a kind of anxious hunger to take in the details of the season before it all vanished away. My internal clock sprang into action: an awareness that any part of the spring might be the entire amount that one is going to get. A sense that one’s small personal world can fall apart; or be taken away; or that one might have to choose to leave it behind, because something else matters more.

All of that was shaping the experience of the apple trees’ first tiny brown bumps that eventually would turn into buds, and the first hints of red leaves on the rose bushes, and the slender green tops of the tulips whose colours weren’t yet visible.

Now the end of April has come, and spring is fully underway. The anniversary is past. The bumps on the apple trees turned pink, then began to show hints of petals, and now are within a day or two of opening fully. The tulips opened three days ago: they are a magnificent red, with orange pistils at their centers.

In the forest, the vitsippor (white anemones) have opened. If one drives with friends alongside a forest’s edge and sees a cluster of them, as I did the other weekend, the car will slow down so that everyone can look. The vitsippor are protected wildflowers here: it is illegal to pick the blooms or to uproot an entire plant.

I have a different protected flower in my garden, planted there by my neighbor W. one afternoon when I was away. He wasn’t sure what it was called, but a few bulbs of it had been given to him by a woman some decades before, and were now among the most prized flowers in his own garden. The flowers could no longer be bought or sold, he said, but it was all right to give them away, and he wanted some of them to move across the street into my garden.

That was in the fall after I returned after my father’s death. I wasn’t really functioning, and couldn’t give W. the kind of daughterly attention that I had been giving him before then. I didn’t resume our daily walks, and I stopped serving coffee to him and the other neighbours every day, a custom that had begun when I moved here during the pandemic, in the time when sitting outside and talking, or taking walks and talking, were the only safe ways to be around people outside one’s own household.

That autumn and winter W., who had lived almost without illness his entire 79 years, had everything catch up with him at once. He grew ill, and the neighbors cared for him, along with his family who lived a little further away. W. was a stubborn old goat, as one says in Swedish, and he decided what care he wanted, and how much. In the last days before he went into hospice, when he could barely walk, and we had all been going to him at his house, he somehow made his way to my door. He had done the same with some other neighbors just before, as it turned out. He sat in the comfortable chair in my kitchen, and tried to drink the tea that I gave him, but his body couldn’t take it and he wretched into the sink while I rubbed his shoulders.

William had lived alone almost all of his life; I’m not sure that he had had someone to rub his shoulders while he was sicking up for many years. Then he sat in the chair again, and asked me if my father had had many friends; I’m not sure what he was wondering. Finally he asked if I was “glad for the visit” — if I was glad that he had come. I said yes, that I was always glad to see him, always.

W. passed away in hospice a week or so after that night. It was February. I had been to see him almost every day, and so had others; he had a constant stream of relatives and people from the village, most of whom had known him as s fixture here for every day of their lives. I was able to give him things simply, as he was dying, in a way that I hadn’t been able to for my own father less than a year before.

I forgot about the protected flowers that W. had planted until one day when green shoots began to appear where otherwise there was nothing. W. had placed them under an area of small stones and then replaced the stones, so the green poking up through them stood out as stunning and unexpected. The stems grew up into some kind of lily, maybe a tiger lily. I’m not actually sure that they’re as special as W. believed they were; they might not even be protected. But they are there, and this year they have come again, and later in the summer they will likely bloom.

W. is buried in the churchyard outside of town, beside his parents and near his brother. I’ve stopped by his grave a couple of times, and put a wildflower or some such thing there, and when I have I have sometimes thought of Victor Hugo’s poem about setting wild flowers onto a grave: never the whole poem, but just the last line, which reads “and when I arrive, I will set on your tomb/a bouquet of green holly, and of heather in bloom.”

Hugo’s poem is about a father who has lost a daughter in her early adulthood, and I could not think of it in terms of my own father and my loss of him. There was too much pain involved, and my father had not been able to be towards me the way Hugo was towards his daughter, though he so badly wanted to.

But oddly, a month or two ago, after I published an essay that included a mention of my father, the first time I had ever written about him in public, I heard his voice in my ear, the way one hears the echo of a voice, from very far away. It said simply “It’s ok,” and added an endearment for me that he had used when I was very small. It felt as though, after death, all of the layers of pain and other things that he had felt and that had interfered with that simple, loving father-ness had dissolved, and there he was, in a distance, being generally kind, generally reassuring, generally a father being a father.

When the anniversary of his death came around last month, the poem came back into my mind, and for the first time I could think of the whole of the poem in connection with my father. Not as a mourning poem for him, though that was there, but as an image of him as someone who loved me, an image that felt congruent with what perhaps was always there, just hidden under the difficult layers of other things.

Here is Victor Hugo’s poem, and below that is my own loose semi-prose translation, followed by some commentary on the translation choices.

The poem

Demain, dès l’aube

Demain, dès l'aube, à l'heure où blanchit la campagne, /Je partirai. Vois-tu, je sais que tu m'attends./ J'irai par la forêt, j'irai par la montagne./ Je ne puis demeurer loin de toi plus longtemps.

Je marcherai les yeux fixés sur mes pensées,/ Sans rien voir au dehors, sans entendre aucun bruit,/ Seul, inconnu, le dos courbé, les mains croisées,/ Triste, et le jour pour moi sera comme la nuit.

Je ne regarderai ni l'or du soir qui tombe, /Ni les voiles au loin descendant vers Harfleur,/ Et quand j'arriverai, je mettrai sur ta tombe/ Un bouquet de houx vert et de bruyère en fleur.

(Source, plus additional information: fr.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demain,_d%C3%A8…)

My translation

Tomorrow, when dawn comes

Tomorrow, when dawn comes, in that hour when the countryside grows pale, I will set out. My dear, the thing is, I know that you are expecting me. I will make my way through the forest, I will make my way through the mountains. I cannot be far from you any longer.

I will walk with my eyes fixed upon my thoughts, seeing nothing beyond, hearing no sound, alone, unrecognized, back hunched, fingers laced, desolate, and for me the day will be like the night.

I will take no notice of the gold of the setting sun, nor of the distant sails as I descend towards Harfleur; and when I arrive, I will place on your tomb a bouquet of green holly, and of heather in bloom.

Notes on the translation

*My dear, the thing is. It is hard to capture of the shock of the sudden intimacy and casual tone of Hugo’s “vois-tu,” which is usually translated as “you see.” I’ve ended up replacing the entire phrase with something that I hope comes close to it.

*I will take no notice of. Literally: I will not look at.

*As I descend towards Harfleur. Literally: Descending towards Harfleur.

The grammar and rhythm of the poem both push towards it being the sails, not the speaker, that are “descending towards Harfleur,” and that is how the text is generally read, so far as I can tell.

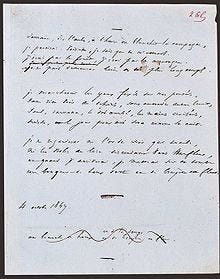

As I was translating it, however, it occurred to me how much the image that I have had, in the forty or so years that this poem has lived in my head, has been of the speaker, not the sails, doing the descent towards the harbor at Harfleur. As it happens, the grammar (sort of, almost) allows that reading too, even if it is not the immediate one that one would make. And Wikipedia has an image of the first, handwritten draft of the poem that shows a distinct space between the sails and the word “descending” that does not show in any printed version.

Presumably all of this has been discussed in scholarly literature — this is among Hugo’s most famous works — but I don’t have access to that just now, so you are only getting my own idiosyncratic take.

Hugo’s daughter was 19 and recently married when she, her husband and their unborn child died in a boating accident on the river. Hugo made annual trips to her grave. You can read more about the poem, and find an English-language translation of it, along with the image above, on Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demain_dès_l%27aube.

My father’s ashes aren’t buried yet, but there is a magnficent cemetery in Cambridge where one can choose a tree and place a memorial marker and inscription there. We will choose one of those one day soon. My father, a Buddhist, would have liked that, I think. A memorial that is connected to a tree rather than stone speaks of life, and memory, but also of impermanence, of moving forward, of dissolving and gently re-forming into something new, something that nourishes and loves and inspires but still is a different thing, as with a tree when it eventually falls.

If you missed my previous post, you will find it here:

A translated poem, and memories of the poets Kenneth Koch and Brigit Kelly

A very long time ago I took a course in twentieth century poetry with the poet Kenneth Koch. It’s funny how some things stay and others vanish. I remember moments of that course strongly: one of them was Koch’s irritation, after assigning Yeats’s “Down by the Salley Gardens,” that no one in the class had bothered to…

If you would like to see an illustrated discussion of the idea of “between hägg and lilac,” by

, you will find it here:

Beautiful

So beautifully written! Touching and thought-awakening. Wonderful how you connect life events with nature’s cycles and our relationship with them. Thank you for sharing.