While Riding on a Train Going West

Diary of a trip from Massachusetts to California

In a recent essay, “Milosz in California,” I mentioned a long train ride from Boston to California.

In case anyone would enjoy it, here is a lightly edited version of the travel diary from that train ride, which I wrote at the time (more than ten years ago) for family and friends. The ride was three days and three nights.

I chose to do the trip in an assigned seat, rather than a sleeping cabin, as I wanted to be around people, and those with cabins could not be sure of a seat in the public spaces during the day. Thus all the talk of seat-mates.

Travel Diary

It's Friday noon and I am off on the Chicago-bound train from South Station, Boston.

This is basically the same type of train that I take all the time from Boston to New York, except with more legroom and footrests. Not in any way interesting or exotic.

Friday afternoon and evening we roll through Massachusetts, stopping for long stretches due to engine or signal failure. One stop has us paused for about 25 minutes in front of a grove of what look like giant fern trees. I call my friend M. to get her to look them up for me, and to confirm that ferns are among the oldest plants on earth.

In Albany, finally. Here the Boston-to-Chicago train merges with the New York-to-Chicago train, and the two travel together through to Illinois. The New York train brings a formal dining car, but I don't bother to check it out.

At some point that night we enter Ohio. We pass through mostly at night, coming up to Cleveland just before dawn.

Saturday dawn: an enormous dense bank of cloud off to our right, in an otherwise clear sky. Except that it's mostly perpendicular to the earth. This is a monstrous, muscled, titanic cloud, trailing bits of grey. It starts long and low and horizontal off to the left then rears into the air, gaining in height and size and losing its attachment to the earth. It might be smoke.

Eventually we pass the source: the cloud is not smoke, but fog, beginning to burn off of Lake Erie, just past Cleveland.

We arrive in Chicago at 11 AM, enough time for me to have an excellent vegetable panini and soup for lunch and buy some good penne in marinara sauce to take onto the real train of this trip, the California Zephyr, which runs between Chicago and San Francisco.

The CZ is lovely. Most cars have two decks, and most seating is on the upper deck. Everything is pristine. Each car has its own attendant who manages it, handles the doors at stops, and generally serves as a guide and reference point throughout the trip.

I think idly that if one were to outfit a train today to match the great luxury lines of the gilded age, one would add a yoga car, with sessions led by a instructor. Then I think of what could happen if the train lurched or rocked during certain poses.

Saturday afternoon, in Illinois then passing into Iowa. Corn fields everywhere, but the corn is surprisingly low -- not more than knee-high. No other plants are in sight except stands of trees that serve as windbreakers for the farms. Sometimes an empty road crosses an empty cornfield and you think, Hitchcock owns this. After “North by Northwest,” this scene is his.

Occasionally, a red-winged bird flies low over the fields. It's the only kind of bird I see anywhere in Iowa. The land isn't actually flat -- it rolls, with many low rises, not quite big enough to call hills. In England one might think that they had barrows underneath.

My seat-mate is traveling from Albany to Iowa to see an elderly man who flew reconnaissance planes with her father in the Japanese islands during WWII.

At Burlington, Iowa, we cross the Mississippi. My seat-mate generates some mild interest to match my own, but no one else seems interested in the crossing.

This far north the river is not unusually wide -- perhaps less so than the Hudson by Manhattan -- and it flows swiftly. It feels like a brisk Iowa river. I picture it downstream, getting bigger and wider and more filled with painful history. For some reason, I never expected to see the Mississippi River.

We travel in dense fog throughout the night in Nebraska. There is a sense of completely flat country, but that is guessing from the ten feet or so that one can see on either side of the train, before the fog walls off the rest of the state.

The fog stays with us into Colorado and the start of Sunday.

Early dawn Sunday we pass through a rural Colorado town. The first backyard we pass has four or five small, old trucks parked in a row. They look to be from the 1950s. Then a few moments later the next house and yard, this one with two trucks, also from the fifties. The houses are small, square, in faded colors. There are no modern cars, or modern anything, in sight. Half awake, I wonder whether the train has carried us through time as well as space. The next yard holds one truck and a sedan, both from the fifties. Finally, after that, a set of muscle cars from the sixties, then a square-backed pick-up truck -- when were those first made? Relieved that we have not traveled back in time, I go back to sleep.

An hour later, just after dawn, I am in the observation car. We have a couple of hours still before we reach Denver. A grandmother is trying to distract a bored small grandson by getting him to count rigs as we pass. In the observation car the seats swivel 360 degrees, to allow viewing on both sides of the train.

We pull close to Denver. The woman next to me in the observation car, who used to live in Estes Park, asks me, disturbed: “Where are the mountains?” We both look.

We have both been in this area before, and know what we should be seeing: the Rocky Mountains, dominating our world. Instead, we have to peer even to get a sense of them. They are almost invisible, the foothills barely outlined through a blackish mist that is likely darkened by smoke from the huge wildfires near Fort Collins. Later I hear that friends in these mountains have been evacuated.

At the station I take a picture of Denver, the closest I will come to Boulder this trip.

On the way from Denver to the mountains I talk further with the woman in the observation car. She has grey hair. She brings up that she is native American, but doesn't mention which tribe. We talk about the Coyote trickster stories, which she has heard told by master storytellers in both Navaho and Ojibwe (I think it is) languages She knows enough of both to listen and understand, but not to retell the stories herself. She tells me about her experience weaving with strips of black elm, soaked first to make them pliable.

As we start the climb up the mountains the observation car is packed. A park ranger tells us that these are in fact the New Rockies. The original mountains, the first ones created when the plates collided, have already eroded away and now lie flat beneath these newer mountains, which were created by further movement of the earth plates here. The old-feeling mountains of the East, like the Green Mountains of Vermont, are just a little younger than the Old Rockies that have already been worn into dust.

The view down is too vertiginous, and I go back to my regular seat. From here, sitting on the aisle instead of my usual window, I mostly see up and over, but not down into, the inconceivable drops beneath us.

After a climb in the sunlight through stunningly beautiful mountains, all green (we stay below the tree-line), we reach the Molson Moffat Tunnel, which runs directly under the principal pass in the Continental Divide. The tunnel takes 10 minutes. This is the pass that people in covered wagons died getting over. It took us two hours and ten minutes to reach and traverse it, in air conditioning.

I mention this thought to my seat-mate, a new college graduate who came on in the middle of the night before. She tells me that her great-great grandparents, on all four sides, had been part of the original group of Mormons that traveled over the mountains with Brigham Young to Salt Lake. They had gone via Wyoming, not this pass, but it was an similarly arduous journey, and they had all kept detailed diaries of their journeys, including the losses of children, which she had held in her hands and read. She feels sure that those travellers who survived the early transits would not, as I had half been worrying, have resented our later effortless crossing. They would have been glad.

After the summit we track the Colorado River to Frazier, then Grandy, then through a huge national park. From the observation car I see isolated cabins with kayaks but no cars, and people camping beside or rafting or kayaking on the river.

Much of this land is a canyon, only accessible by foot, kayak or train.

In the cafe, I eat my second cheese-and-cracker plate of the day. The cafe car is out of frozen pizza, to which I had been planning to diversify, and is looking to run low on bottled water as well. It will not replenish before SF. But not to worry: I am the only one buying cheese plates, the bartender says. And I have a duffel bag full of food back at the seat.

In the observation car, a grandmother from a farm in Iowa with whom I’d chatted earlier taps me on the shoulder to share something new to her: a fellow passenger reading on a kindle in Japanese. I smile politely.

Later I will do the exact same thing to my Utah seat-mate, tapping her on the shoulder to share the sight of three long-horned cattle drinking water at a river. She will be as polite as I was about the non-English kindle book; this sight is ordinary to her.

Into Utah. First, extraordinary rock canyons of huge, red, stone, lava-like cliffs. Not buttes, because made of rock rather than earth; and often what looks like a freestanding plateau of stone is actually a continuous wall. We parallel a river running between these walls. I am terrified. It is 100 degrees Fahrenheit outside. If the train breaks down, we will be lost in the heat under these huge, alien red rocks.

My seat-mate is quietly rejoicing. She has often hiked these canyons; this land is home.

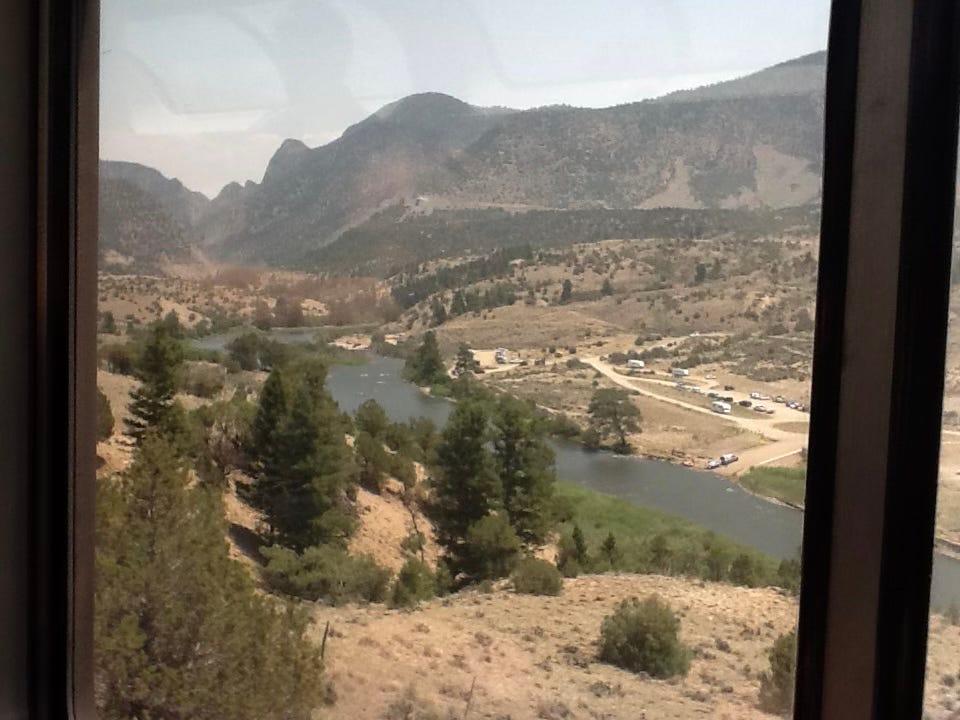

I am too intimidated among the rock canyons to take photos. We emerge from Ruby Canyon into this:

First the desert, then what I think is tundra, though my knowledge of this kind of land is shaky; then desert again, miles and miles of brown earth with gullies, arroyos and odd little rises, towered over at the edges by new, different barren cliffs. Settlers traveled this too. Someone in one of the cars, or maybe something I have read, said that in the red rocks of the canyons, a Native American people, whose name I did not get down, once lived in rock caves. Even in the full desert, there is water under the earth if one knows where to look, and sometimes it rains.

Some of what I have been thinking of as arroyos are deeper than a walking man or woman. Others, which I might call channels, are more like low ditches. All are perfectly dry. My seat-mate says that people who are from here, like her, don't call them channels or arroyos or gullies. They call them dry creek beds, and know when it is safe to walk in them without risk of drowning.

Sunset in Utah. Perhaps ten minutes, no more, between the first rays of red and total darkness. In the dark, a stop at Provo; then, at nearly midnight, at Salt Lake City, where every empty seat in the car fills up, including the one next to me, as the Utah seat-mate has finished her trip by now.

At late-night stops on the two earlier nights the conductors have assigned seats to incoming passengers, allowing them to swiftly find a place to settle down. For some reason that does not happen tonight, and six or seven people walk up and down the car on their own, looking first for easily-accessible seats and then giving up and waking those who are sleeping across both the two in their rows. Several rough-looking guys with extensive tattoos are among them, and I am relieved when the first person to ask for the seat beside me is a man in a baseball cap who, although substantial, so that he will crowd me in my seat, is polite and calm.

Too ratcheted up on the thought of San Francisco tomorrow to sleep, I stay up listening through earphones to Bob Dylan: "While riding on a train going west, I fell asleep for to take my rest…"

Before dawn I sneak over my new seat-mate to brush my teeth and sit alone in the observation car. I also change clothes.

We come into Nevada, a couple of hours before Reno, just after dawn. This is a continuous moonscape of low brown hills. At first they look bare and barren. Later I see that they have the same brown grass and low scrub as the meadows (is this what is meant by a living desert?) around them. The grass must be growing, because cows are grazing on it in little groups, one with a white calf nursing on a black cow, so that at first it looks as though the great cow is black above and white below.

I take up my list of essential and desired places to go in California. I still haven't decided about people in Bolinas. Part of me wants to contact those I have facebooks links with, and through them anyone else who might remember me from there, or whom I might remember. Another part just wants to go and see.

We reach Reno. After Reno we cross the Truckee River, going towards the Sierras, and suddenly there are pine trees everywhere. This feels like home.

Over the loudspeaker, the conductor announces that the Truckee was the Nevada-California state border. We are now in California. All through the climb up the Sierras I am surrounded by the light and colors and trees of home. We backpacked in these mountains, in grade school, and I spent a whole summer in summer camp here, the year before we moved away. I am overwhelmed.

An hour into the Sierra Nevada I go back to my own seat and sleep. I wake to the announcement that we are passing near Sutter's Mill, where gold was found in 1849.

I start talking to my middle-of-the-night seat-mate. He turns out to be a fellow academic. We discover people in common. He gets off shortly afterwards.

It is 3 pm, and we are due to arrive at 4. I start to pack up my things.

3:45 pm: last stop before Emeryville, from which it is a half-hour shuttle bus to San Francisco. Coming up the bay to Emeryville, I catch a glimpse of Mt. Tam.

A moment later, Mt. Tam is straight ahead of me for a long stretch.

Many thanks to

, , , , , , , , , , , , and Mil Bil for recommending Pen, Book and Garden: Notes from Linnesby to their readers.

Loved this. There’s something magical about long train journeys. The stream of unfolding landscapes. The steady beat of soporific sounds. The dreaminess of it all. 🌿🎶

Have you seen the photographs taken by Katie Edwards, through a train window? She is on Facebook and Instagram.

She says “I thought of the train as a sort of mobile chronotope, providing a continuous thread through which diverse places and moments were interconnected. Each photograph taken from the train window would be a fragment of a larger narrative, where the journey itself became a storyline that traversed different geographical and cultural landscapes. The compression of space into a confined train window frame, juxtaposed with the slow unfolding nature of a train journey, allowed me to experience and document the nation in a way that captured both the immediacy of the present and the continuity of travel over time.”